Squalid Calculations

When I made my living by fishing eels I sometimes had them smoked by a well- known game and fish dealer in town. When I collected them they would be bunched by a piece of string through their gills, and the simplest way to carry them was to hold the string and let them dangle.

Responses varied. Some people were startled or repulsed; occasionally someone caught off-guard might scream. But if my trip to town took me into an up-market estate agent’s where the front-office staff were suitably-posh young women, they were likely to cry out: ‘Smoked eels! Scrummy’!

The British may be unique in Europe in having been permanently colonised. We – if you identify with the Anglo-Saxons - were invaded and became the underclass ruled by people from another country, speaking another language, and very definitely in control, ruling us from a network of fortresses. After 1066 the Norman-French automatically became the ruling class. From their castles they developed a racially-based system of controlling the natives in the southern half of England, and simplified the problems of controlling the north by a genocide - ‘The Harrying of the North’ - that is thought to have left at least 70% of the northern people dead. The deeply-entrenched class system very peculiar to the UK must surely stem from the Norman Conquest – no other European country was colonised in this way - and to this day the posh girls crying ‘Scrummy’ and the working-class girls horrified at the sight of smoked eels are the inheritors of this division between the French-speaking aristocracy and the Anglo-Saxon-speaking peasants.

Class division, fundamental to English life and English thought from the moment of the Conquest, was also applied to animals, and to plants. All animals were either game or vermin. The British upper classes have delighted in eating all manner of wild animals, and in this new arrangement of Norman-French aristocracy and Anglo-Saxon peasants, they came to reserve to themselves the wild boar, the venison, the snipe and the grouse, hares, rabbits and every other delectably edible wild creature. The posh people ate game, the posh food, and the peasants were not even allowed to eat rabbits. In a past without most of our favourite vegetables – when potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, sweetcorn and aubergines were still ‘undiscovered’ in the New World or in Asia - the peasants had to eat bread and cheese, peas, beans, cabbages and turnips, and the few wild foods such as blackberries and mushrooms not requisitioned by the upper classes. For centuries the forest laws and game acts made it illegal to hunt, or even to possess hunting dogs, nets, traps or guns, unless you were a wealthy landowner. For hundreds of years the country people risked transportation or even hanging for poaching offences. Often they were caught ‘poaching’ where their ancestors had hunted, before the Enclosure Acts took away their ancient rights to the village lands, wastes and commons. The Enclosure Acts and the game laws converted the still partially hunter-gathering peasants into poachers, and poaching became perhaps the most persistent guerrilla resistance against the overweening aristocracy even into very recent times.

Any animals not seen as game and reserved for the aristocracy were generally classed as vermin. Under the Vermin Acts of Elizabeth I each parish paid bounties for the killing of ‘vermin’ as innocuous as bluetits. Wild creatures and plants were just as subject to the class system as the common people. Most animals were seen as vermin, even trees were divided into the noble trees, such as the oak, and trees with less grandeur which were called scrub. Viewing our biodiversity through the lens of class has done huge damage and even now obstructs the development of more enlightened attitudes to natural ecosystems, and perpetuates the view of the natural world as existing to enrich and entertain the landowning class.

Somehow fish seemed to have escaped the attention of the aristocracy until the fashion for sporting estates took off in the 19th century, leading to the Freshwater Fisheries Act of 1878, when salmon and trout, having suddenly become noble upper-class fish reserved as far as possible to the fly-fishing aristocracy, were protected while the inedible fish such as chub were left to the working-class fisherman. Near my childhood home the fishermen of the riverside village of Hoarwithy had had what was undoubtedly a common right since time immemorial to use nets to fish for salmon from coracles on a stretch of the River Wye as it passed the village. Lord Edwyn Francis Scudamore-Stanhope, a local landowner and 10th Earl of Chesterfield, when salmon fishing became part of the sporting life of the newly-fashionable country estates, attempted to extinguish this ancient right. The fishermen fought him all the way to the House of Lords. They lost, of course, as did the few commoners who had occasionally tried to challenge the enclosures of their lands by appealing for justice to a parliament of enclosing landowners.

The only other fish which managed perhaps characteristically to evade social classification at least until recently was the eel. The reasons for this are complex and interesting. Eels were once extraordinarily numerous in a wilder and more watery countryside, more numerous than all the other freshwater fish combined. When Britain was a Catholic country everyone had to eat fish on Fridays and during Lent, and so it was a religious necessity that fish should be available to all regardless of class. Eels could usually be caught locally; they could be kept alive until needed, and they could be preserved by a combination of salting and drying. Monasteries and other religious houses in particular needed a plentiful and reliable source of fish, and eels were seen as suitable for fast days and Lent, being thought unlikely to inflame carnal passions. Monasteries seem to have sorted their fish supply by making their tenants, and millers in particular, pay their rent in eels.

Since paying rent was one of the major ‘cash’ transactions in a very self-sufficient economy with limited coinage in circulation, eels became in effect a form of currency. The commonest rents paid in kind in the Domesday Book were paid in eels, and like most currencies eels had denominations, so that 25 eels were called a ‘stick’ and 10 sticks were called a ‘bind’. These eels were generally salted and dried, and although possibly not very palatable by modern standards, we know that people often came to like the salty foods of the past, such as salt cod, salt herring and very salty home-cured pork and bacon. For much of the medieval period everyone ate eels; there are records of large quantities being procured for royalty and the aristocracy. We don’t know how many of these were eaten fresh; the peasants probably ate many of them as soon as they were caught, but the big catches of the silver eel run every autumn would have had to be preserved, and were most likely to have been used to pay rents, particularly by millers who also often ran the traps for the migrating eels.

At some point the eel economy seems to have collapsed, with catches of eels declining due probably to fenland drainage, and the aristocracy seem to have lost their taste for eel, which remained a working class favourite especially in London. In the late 1800s a new method of preparing eels was developed in Germany – hot smoking – and smoked eels became an expensive delicacy. From this point the English predilection for dividing themselves on a class basis took over again and the upper classes ate smoked eel (Scrummy!’) while the working classes ate jellied and stewed eels, a thriving trade in East End eel and pie shops and pubs until recently, and not entirely extinguished despite eels being now a Critically Endangered species.

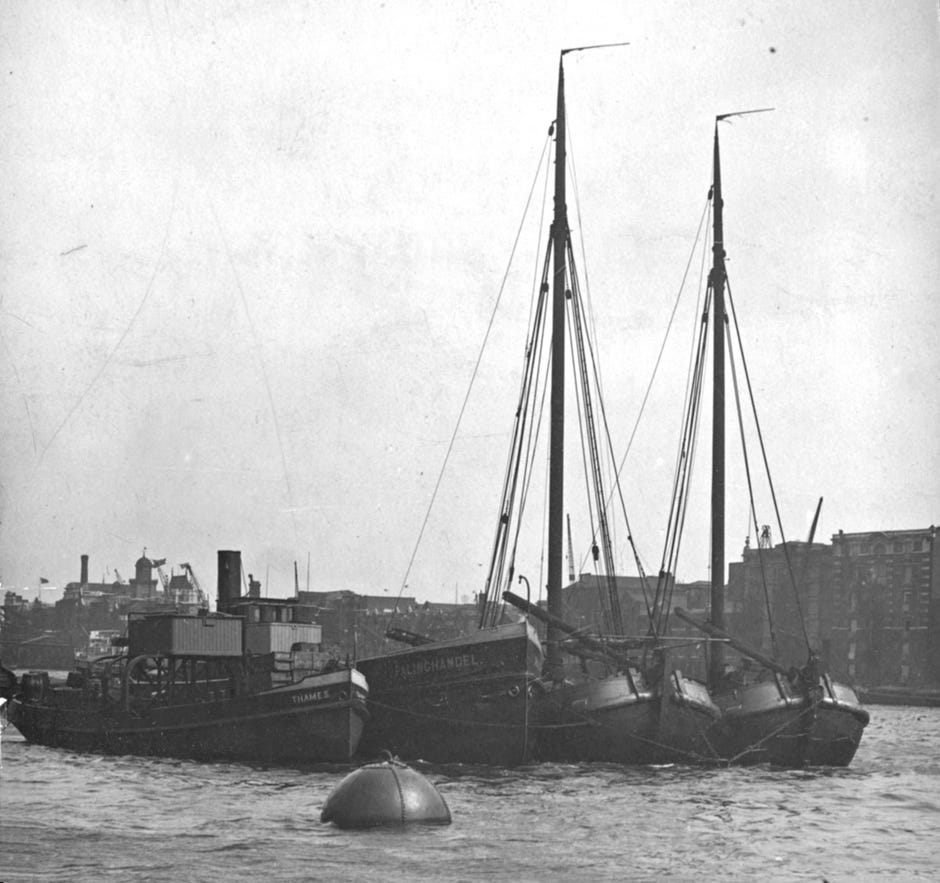

The 20th century collapse in wild eel stocks is not then the first time scarcity due to overfishing and destruction of habitat has affected eel markets. London’s eels originally came from the vast fens of East Anglia. When drainage had turned prime eel-habitat into carrot fields, in a frenzy of entrepreneurial zeal, if you will, or the most dramatic man-made ecological disaster in modern UK history, or arguably both, the Londoners’ predilection for eel was supplied by the Dutch. A small village in Friesland was the centre of this trade. Their ships had holds where water circulated – luckily eels tolerate both fresh and salty water – and their school taught English in order that the men of the village could sail over to London in ships laden with live eels and know enough English to haggle with the Londoners. Their ships were a constant presence, anchored in the Thames at a spot known as the Eel Chains, where they moored offshore to avoid taxation, and where Londoners rowed out to buy their eels. These ships are to be seen pictured on many old maps of London, and they continued to be a presence in the Thames until just before the war, when the last photograph was taken of two of these boats (see above) in 1939, after almost 600 years of trading.

On a recent journey I took from Peterborough to Cambridge the railway line skirted the site of Whittlesey Mere, which was once at six miles across the largest lake in lowland England, 1570 acres of open water set among a landscape of reed-beds, meres, fens, rough grazing and occasional islands. This, before they began to drain it, was a last remnant of the vast fenland extending from Humberside to much of East Anglia, ecologically probably the richest habitat that has ever existed in England. In historic times it would have been home to wolves, beavers and martens and to storks, eagles, osprey, harriers, spoonbills, ruffs and maybe even pelicans as well as huge numbers of warblers and cuckoos and so on. The numbers of wildfowl, of fish and of insects were extraordinary too, and if Whittlesey and the surrounding fens still existed they would be one of the most important wildlife sites in Europe and possibly the world, used on migratory routes by birds of both hemispheres.. The mere had three inland ports and several fisheries; the 1290 Lay Subsidy Roll for Ramsey seems to suggest that upwards of three and a half million eels were caught and their value introduced into the local economy each year by the population of this one small fenland town. The whole area had a richness that it is tempting to compare with the Amazon rainforest, and the local people made a sustainable living from fishing, cutting thatching reeds, wildfowling, grazing and even tourism – it was a popular boating lake and had its own annual regatta. One traveller passed through with a flotilla of three large barges, one for his guests, one for his servants and one for the horses that pulled the flotilla wherever there were towpaths alongside the fenland rivers.

The fenland communities and ecosystems were destroyed because the aristocracy used Acts of Parliament to legislate away the communal land rights of the English peasantry and fenmen, in order to legitimize the enclosure and drainage of the land that the peasants had held for many generations. So long established were the fenmen that St Guthlac, himself a Welshman, claimed in about 700 AD that in their fenland fastnesses they were still speaking Welsh, the language of the Ancient Britons. All you now see from the train are endless flat black fields owned by the successors of William Wells of Holne, the local squire who was able to enrich himself and impoverish the rest of us by draining Whittlesey Mere in 1851 and converting it to a featureless expanse of carrot fields, the culmination of centuries of Fenland enterprise or ecological destruction according to your point of view.

This drainage was the result not only of greed and abuse of power but also of an overly simple profit and loss calculation. On one side of the balance sheet the predicted cost of pumping and draining, on the other side the predicted profits from each acre of carrots grown, or the rent charged to tenant farmers, and the time taken for the investment to be repaid. There was nowhere in that accounting to factor in the rights of the indigenous people, no way of thinking about the value to humanity of pristine places, of abundant wildlife, of carbon sequestration, of sustaining the huge flocks of the wading birds and wildfowl of the world wheeling around the skies, and all the other features that are of a value so indefinable that they were beyond the comprehension of the accountants. (It is even possible that in the national consciousness of the period wild places were seen a harbouring an evil that needed to be tamed and civilised, much as the American settlers felling forests thought they were letting the good Christian light into the darkness of the forests. One pamphleteer on the enclosing side compared the fenmen with the Cherokee).

In 2010 Natural England published a report researched by Cranfield University, on the management of lowland peatland for environmental reasons, which attempts more complex calculations. In a very detailed analysis of possible ways of managing remaining peatlands, it concludes that while some farming systems can conserve any remaining peat, only taking peatlands out of agriculture can result in actual peatland restoration. Their calculations show that setting the value of arable cropping against the cost of agricultural subsidies on peat fenlands there would be an annual benefit from ending agriculture of £200-£500 per hectare, while the average benefits associated with ecosystem services on restored peatlands if farming ceased would probably range between £550 and £2000ha/year. They also conclude that if the fenlands were taken out of agriculture the impact on future food security would be negligible because the depletion of the peat soils is continually reducing their importance as food producing areas. The peat soils have largely shrunk and blown away. In places we are nearly down into the raw clay below Another study, led by academics at Cambridge University together with the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds (RSPB), suggests that the economic benefits of protecting nature-rich sites such as wetlands and woodlands outweigh the profit that could be made from using the land for resource extraction, according to the largest study yet to look at the value of protecting nature at specific locations. The study concluded that the asset returns of “ecosystem services” such as carbon storage and flood prevention created by conservation work was, pound for pound, greater than man-made capital created by using the land for activities such as forestry or farming. The land is kept farmable by constant pumping and maintenance of dykes and sluices paid for by the taxpayer, not the farmers. If the farmers were paying the true cost of maintaining this drained fenscape they would have got out years ago.

We can use the tools of the accountant to reverse past calculations and demonstrate the cash value of ecosystems and ecosystem services, but to use such methods to put a new cash value on ancient or rewilded fenland, and to include an estimate of the cash value to people of recreation and spiritual solace in such places, seems a deeply squalid enterprise. The value of such extraordinarily rich and diverse ecosystems should be obvious, were we not so shackled by values generated in a past of greed and ecological ignorance. That we should have to argue thus to make the case for undoing the ecological devastation of our fenlands says much about the attitudes of the UK landowning lobby.

Knowing how we view property rights as sacred, and how farming is the most effective political lobby in Britain by a country mile, the restoration of the fenscape will be painfully slow. The sea may do what the farmers cannot contemplate when it finally overtops the dykes. Ironically the return of the fens to carbon sequestration might be the most effective way the farmers can contribute to combatting the global warming that will almost inevitably recreate the fens despite them.